SCARBOROUGH — John C. Houbolt, an engineer whose contributions to the U.S. space program were vital to NASA’s successful moon landing in 1969, has died. He was 95.

Houbolt died Tuesday at a nursing home in Scarborough of complications from Parkinson’s disease, his son-in-law Tucker Withington, of Plymouth, Mass., confirmed Saturday.

As NASA describes on its website, while under pressure during the U.S.-Soviet space race, Houbolt was the catalyst in securing U.S. commitment to the science and engineering theory that eventually carried the Apollo crew to the moon and back safely.

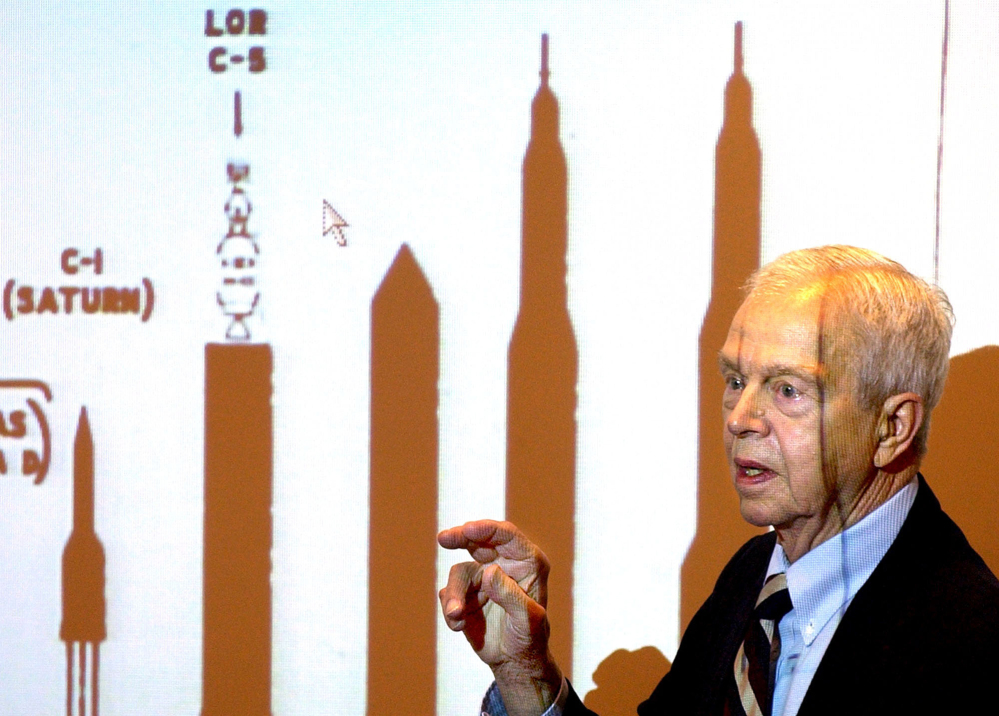

His efforts in the early 1960s are largely credited with persuading NASA to focus on the launch of a module carrying a crew from lunar orbit, rather than a rocket from Earth or a spacecraft while orbiting the planet.

Houbolt argued that a lunar orbit rendezvous, or LOR, would not only be less mechanically and financially onerous than building a huge rocket to take man to the moon or launching a craft while orbiting the Earth, but LOR was the only option to meet President John F. Kennedy’s challenge before the end of the decade.

NASA describes “the bold step of skipping proper channels” that Houbolt took by pushing the issue in a private letter in 1961 to an incoming administrator.

“Do we want to go to the moon or not?” Houbolt asks. “Why is a much less grandiose scheme involving rendezvous ostracized or put on the defensive? I fully realize that contacting you in this manner is somewhat unorthodox, but the issues at stake are crucial enough to us all that an unusual course is warranted.”

When engineers first started evaluating how to reach the moon and return safely, the concept of rendezvous was rejected as too complicated and risky, according to NASA.

At its core, the concept relied on one large rocket to propel three connected craft into lunar orbit. Once circling the moon, the lunar lander would detach and land on the moon’s surface. When the moon walk was complete, astronauts would blast away from the craft’s base and legs to rejoin the command module that remained in moon orbit, NASA says on its website. Then, once reconnected, the astronauts would return to Earth in a tiny capsule that hurtled into the atmosphere at about 25,000 miles per hour.

Different from earlier proposals, the lunar rendezvous model required astronauts to perform the most complex and dangerous parts of the plan – the separation and reconnection of two space craft mid-orbit – far from the relative safety of Earth’s orbit, according to NASA.

“Thousands of factors contributed to the ultimate success of Apollo, but no single factor was more essential than the concept of lunar-orbit rendezvous,” said a NASA historical report prepared by Dr. James R. Hansen, author of a history of the agency’s early development. “Without NASA’s adoption of this stubbornly-held minority opinion, we may still have gotten to the moon, but almost certainly it would not have been accomplised by the end of the decade, as President Kennedy had wanted.”

Houbolt started his career with NASA’s predecessor in Hampton, Va., in 1942, served in the Army Corps of Engineers, and worked in an aeronautical research and consulting firm in Princeton, N.J., before returning to NASA in 1976 as chief aeronautical scientist. He retired in 1985 but continued private consulting work.

Born April 10, 1919, in Altoona, Iowa, Houbolt grew up in Joliet, Ill., and earned degrees in civil engineering from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He earned a doctorate from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology at Zurich in 1957.

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.