The patient, who had cancer, had come down with some flu-like symptoms.

It was 2008 and Tim Borelli, now a physician who specializes in infectious diseases at MaineGeneral Health Center in Augusta, was in his fellowship at the time.

“She had an illness,” he said. “It was kind of nonspecific.”

The patient’s symptoms ordinarily wouldn’t be cause for alarm, but because the woman was weakened by cancer, Borelli took them seriously.

“We tested her for all kinds of things,” he said. “We look for all possible causes. We check their lungs to make sure they don’t have pneumonia. We do physical exams. Do they have any rashes?”

Tests of her urine showed nothing. Her X-ray was clear. She had no skin infections or stomach problems.

“Then you have to start thinking about different possibilities, such as viral or tick-borne diseases,” Borelli said. “It was in a summer month. Tick-borne diseases are always things we need to consider. And we learned she had had some tick exposure.”

Some of the blood work showed that the woman’s blood didn’t have enough white blood cells in it. Tests also revealed a high level of liver enzymes in the blood, most commonly seen when the liver is damaged or inflamed.

Taken together, the two things pointed to anaplasmosis.

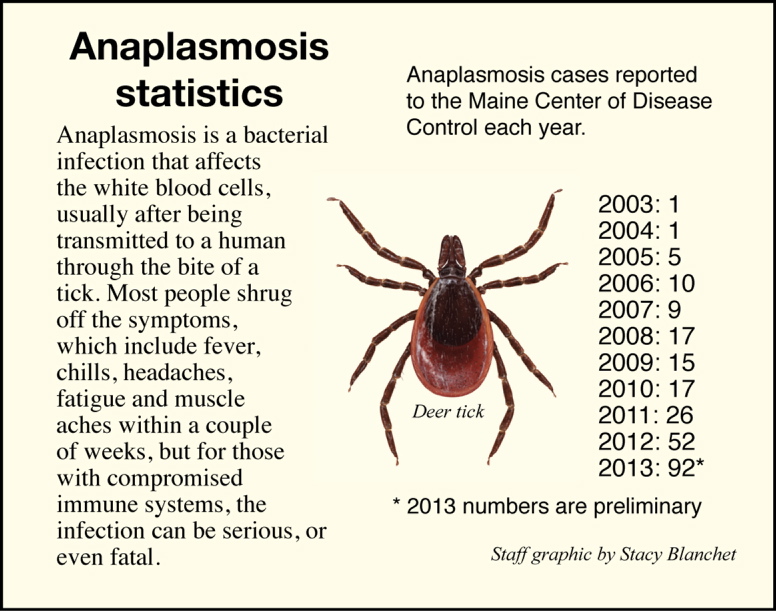

A tick bite usually spurs thoughts of Lyme disease, but a recent rise in anaplasmosis has caught the attention of epidemiologists in the state.

Many people shrug off the effects of anaplasmosis — symptoms can include fever, chills, fatigue, a headache or muscle pain — but in rare cases, especially for those with compromised immune systems, it can kill.

The diagnosis is confirmed most often with a serology test, which tests the blood for very specific antigens — in this case, antigens that the body produces only when anaplasmosis is present.

The woman’s diagnosis wouldn’t have been a problem for the majority of people. Most healthy people don’t even require treatment. A two-week course of doxycycline, the same antibiotic that is used to treat Lyme disease, usually kills the bacteria for those who do need treatment.

But Borelli’s patient’s system was already so weak that it was the final blow.

“She did succumb to that illness,” Borelli said. “That was a sad case.”

The anaplasmosis wasn’t considered the cause of death, he said, but it was a contributing factor.

“Your body’s already being attacked by that cancer,” he said. “The chemo squashes it some more. Then you get an infection that lowers it even further. Then you’re trying to fight that infection with a weakened immune system. That stress, they can’t overcome it sometimes.”

Anyone whose spleen has been removed, who has had a bone marrow transplant or undergone chemotherapy and then gets anaplasmosis is at risk, Borelli said.

About one in 200 people who are diagnosed with the disease die as a result of it, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

TICK ATTACKS LETTERMAN

About a year after Borelli lost a patient to anaplasmosis, David Letterman, host of “The Late Show” on CBS, told millions of viewers in late July 2009 that he was sick, but he didn’t tell them what he was suffering from, touching off widespread speculation about what it could be.

For a few days in a row, he took his temperature on air, which was more than 100 degrees one night and which topped out at 102.5. He joked that the thermometer reading meant someone won $100 in a pool among the show’s staffers.

That Thursday, he told the audience that he was recovering from anaplasmosis, which he said he probably contracted from a tick while spending the night in a treehouse with his son. He said it left him feeling worse than he had in the aftermath of heart bypass surgery.

Letterman’s experience taught many the name of the disease just when it was starting to become more common in the United States, mostly in the upper Midwest and Northeast regions.

First discovered in the country in the mid-1990s, the number of cases has increased steadily.

When Letterman got it in 2009, the Centers for Disease Control reported 1,163 cases nationally, the first time it had topped 1,000 cases. In 2010, nearly 1,800 cases were reported, more than 10 times the number from 1998.

That rapid increase has also been seen in Maine.

Ten years ago, the disease was virtually unheard of in the state, with just one diagnosed case in 2004.

Over the past decade though, the number has been climbing, especially in the past few years. In 2012, the number of cases doubled, from 26 to 52. In 2013, preliminary figures released by the Maine CDC in response to a request from the Morning Sentinel show 94 reported cases, a new high, according to state epidemiologist Dr. Stephen Sears.

In its 2012 annual report on infectious diseases, the Maine CDC said the rise highlights “the importance of awareness and prevention efforts around tickborne diseases in Maine.”

Borelli said that before anaplasmosis was recognized in the United State in the 1990s, most doctors assumed that people with the disease were actually suffering from ehrlichiosis, a very similar tickborne bacterial infection that is commonly carried by the Lone Star tick in the South.

“They’re almost identical, clinically,” he said.

Now, though, doctors recognize that the Northeast has its own unique strain of bacteria that distinguishes itself from ehrlichiosis, creating one more difference, however subtle, between the two regions.

PREVENTION IS KEY

Borelli said the increase in the number of reported cases in Maine is probably at least partially a result of the increase of awareness and improved diagnostics among health care professionals.

“We’re looking for it a little bit more,” he said. “As providers get more educated on tickborne diseases, they’re going to test for it more. The more you test for them, the more you find them.”

Another factor might be the last couple of mild winters, which have been easy on the ticks that carry the disease.

But he also said many people get anaplasmosis at the same time they get Lyme disease. Since the treatment for both is the same, many cases of anaplasmosis probably go unnoticed.

When a person with Lyme disease seems to be struggling with it more than would be expected, it is often a sign that they’ve been co-infected by both bacteria at the same time.

“We don’t get too excited about anaplasma with most people,” he said. “In immunoconfident people, the infection is generally self-limited in a period of time, usually about two weeks. There’s no evidence that it causes any kind of chronic infection. That’s the good news about this disease.”

The CDC recommends that people take steps to avoid contact with ticks by staying clear of wooded and bushy areas with high grass and leaf litter and by walking in the center of trails.

It also recommends the use of tick repellents that contain DEET or permethrin on skin, clothing and items such as tents.

As soon as possible after being outdoors, bathe or shower and conduct a full-body tick check, paying special attention to the underarm, in and around the ears, inside the navel, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist and especially in the hair. Gear and pets should also be checked.

Ticks on clothing can be killed by putting the clothes in a dryer on high heat for up to an hour.

Matt Hongoltz-Hetling — 861-9287 mhhetling@centralmaine.com Twitter: @hh_matt

Send questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.