The 50th anniversary of Margaret Chase Smith’s announcement as a Republican presidential candidate was met in this area with a certain amount of celebration.

After all, Smith is from Skowhegan and is one of our state’s heroes.

Her announcement in 1964 was momentous for many women, young and old — at the time, women had only been allowed to vote for president for 44 years and few had made a stab at running for president.

It’s likely, when Smith made that announcement, that there were fathers who looked at their young daughters and thought, possibly for the first time, that their little girl could be president some day.

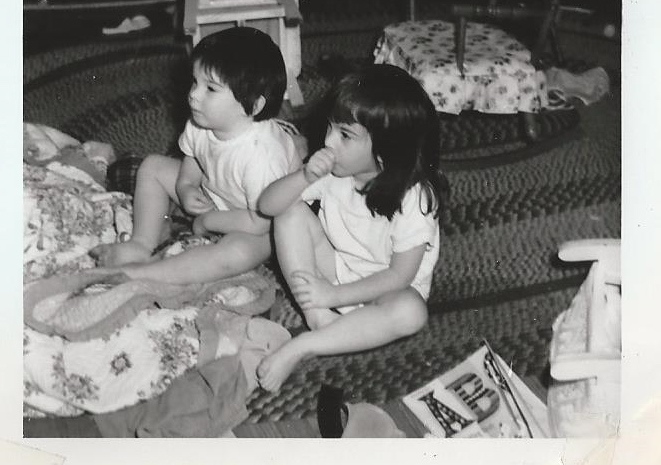

I was three months away from my third birthday when Smith announced. My sister, Liz, was two months from her fourth.

I was seven years from being told I couldn’t be a school crossing guard because I was a girl, eight years away from being told I couldn’t play Little League baseball for the same reason.

Liz wasn’t as inclined to bang her head against concrete walls, and took the more subtle approach. With a thirst for knowledge and the innate belief that knowledge is power, she was about a year and a half away from getting her first in a decades’-long streak of straight As.

Both of us were a decade and a half from graduating from Augusta’s Cony High School and getting bachelor’s degrees from a college that in 1964 was still eight years away from admitting women.

She got a Ph.D. in history and is a college professor. I got an advanced rock âem, sock âem newsroom degree, working my way up to the job I have now.

And yes, we had a world more opportunity than our mother’s generation.

Which makes it even more notable that no woman has gotten any farther in a presidential run than Smith did in 1964.

Notice I haven’t called it historic.

Smith became one of the first women to bring delegates — 27 — to the convention of a major party, thereby putting her name in the hat for the nomination later that year. But Barry Goldwater, with 883, won the nomination on the first ballot and Smith was quickly a footnote.

Don’t take it from me. Ask the one with the Ph.D. in history.

Smith’s run for president and her convention presence “in terms of women’s history does not rank as a major breakthrough,” Liz said this week.

“Nothing came from it. Nothing, as far as a woman being nominated, has happened since. Hillary Clinton came the closest, and that was, what? 44 years later.”

Before the fine citizens of Skowhegan start forming a protest march to my door, let Liz finish.

She’s taught women’s history — as well as “men’s history” — at the college level for more than 20 years. Smith definitely has her place. “I talk about her congressional career and her stand against McCarthyism, that was her historical significance.”

Just so you don’t think this is a Milliken-girl gang-up, I asked Ellen Fitzpatrick, a history professor at the University of New Hampshire, to weigh in, too.

Fitzpatrick points out Smith still made her mark by “challenging her own party to find a place for her candidacy.”

She says the time was ripe for Smith’s move.

“There were, to be sure, many signs of restlessness regarding women’s place in America,” Fitzpatrick said by email this week.

President John Kennedy had appointed a presidential commission on the status of women, which delivered its report in October 1963. The report, The American Woman, “focused attention on the issue of inequality in the workplace and the need to expand opportunities for women,” Fitzpatrick said.

“The idea that there was a âproblem’ regarding the status of American women was in the air. Betty Friedan, of course, published The Feminine Mystique in â63, as well,” Fitzpatrick said.

Fitzpatrick, like Liz, points out that Smith’s influence is far greater than what she did in 1964.

“She had shown remarkable courage at other moments in her life — most notably when she issued her âDeclaration of Conscience’ in 1950, condemning the recklessness of McCarthyism.”

People liked her. “Her support came not from party leaders but from the rank and file and reflected that âordinary’ Americans were perhaps more progressive in their thinking about political leadership than the mainstream national political parties.”

So why haven’t we had a woman president, or even a nominee, since?

“It’s complicated,” Liz says.

She says it’s got as much to do with money and how it drives political campaigns, the country’s power structure, our lack of campaign reform, limits on elections and even our two-party system as it does with gender issues.

Liz points out that other countries, including ones that are not considered feminist hotbeds, like Pakistan, have had female heads of state simply because the process for picking their leaders is based more on the party, less on the individual.

But Fitzpatrick adds that some of those good old gender reasons still hold true.

There hasn’t been a female U.S. president “I suppose for the same reasons women are denied equality of opportunity in many other realms of life. Hardened prejudices, outright discrimination, fear of change.”

“American politics was long seen as the province of men and we forget that of all the demands the first women rights activists made at the Seneca Falls convention in 1848, the vote was the MOST radical of them.”

The 19th amendment, guaranteeing women the right to vote, had only been in existence for two years when Fitzpatrick’s mother was born in 1922.

So what would historian Liz have said to 3-year-old Liz 50 years ago, when Smith made her announcement?

“I would have said that within 20 years you’d have a woman as U.S. president.”

Many women — Smith, countless ones before and after, our mothers and our grandmothers — made their mark.

But pioneer days should be over by now.

If one thing about the past 50 years is true, it’s that the things keeping a woman from being president — like who controls the money and our country’s power structure, fear and discrimination — aren’t going to change unless the guys are invested, too.

Maybe Fitzpatrick’s grandfather and other men in the 1920s expected a different world for their daughters, the first generation born with the right to vote.

Their hopes were probably not much different from some fathers 50 years ago when Smith made her run.

Yet here it is, 2014.

Fathers with 3-year-old daughters, take a minute to imagine — as hard as it may be — what the world will be like for them in 2064.

Then help make it happen.

Maureen Milliken is news editor of the Kennebec Journal and Morning Sentinel. Email her at mmilliken@centralmaine.com. Kennebec Tales is published the first and third Thursday of the month.

Copy the Story LinkSend questions/comments to the editors.

Success. Please wait for the page to reload. If the page does not reload within 5 seconds, please refresh the page.

Enter your email and password to access comments.

Hi, to comment on stories you must . This profile is in addition to your subscription and website login.

Already have a commenting profile? .

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Only subscribers are eligible to post comments. Please subscribe or login first for digital access. Here’s why.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you've submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.